Ancient Egypt developed one of the earliest and most sophisticated clothing cultures. In a climate of blazing sun and dry winds, garments were born from practical need — to cool, protect, and mark identity — and grew into a visual language of religion, status, and afterlife belief.

Origins — how clothing appeared

At the very beginning people used animal skins and simple wrapped textiles. Over millennia, weaving technology advanced and flax cultivation became central to Egyptian textile production; linen — made from flax — became the dominant fabric because it is light, breathable and suited to the Nile valley climate. Archaeological evidence (hanks of flax, woven fragments) shows that linen was produced on a large scale and used for everyday garments and ritual dress.

Early pieces were simple rectangles of cloth folded and tied. Over time tailoring and pleating techniques developed; some archaeological finds (and recently reported ancient garments) demonstrate early cutting and sewing that turned draped cloth into shaped garments. The practical origin — cooling and sun protection — evolved into intentional design: garments that signaled status, profession, and ritual purity.

Purpose of clothing — practical, social, ritual

Clothing in Egypt had three overlapping purposes:

- Practical (climate & work). Thin linen kept the body ventilated in heat. Simple kilts or short skirts were common for laborers; layered garments and cloaks provided warmth when needed.

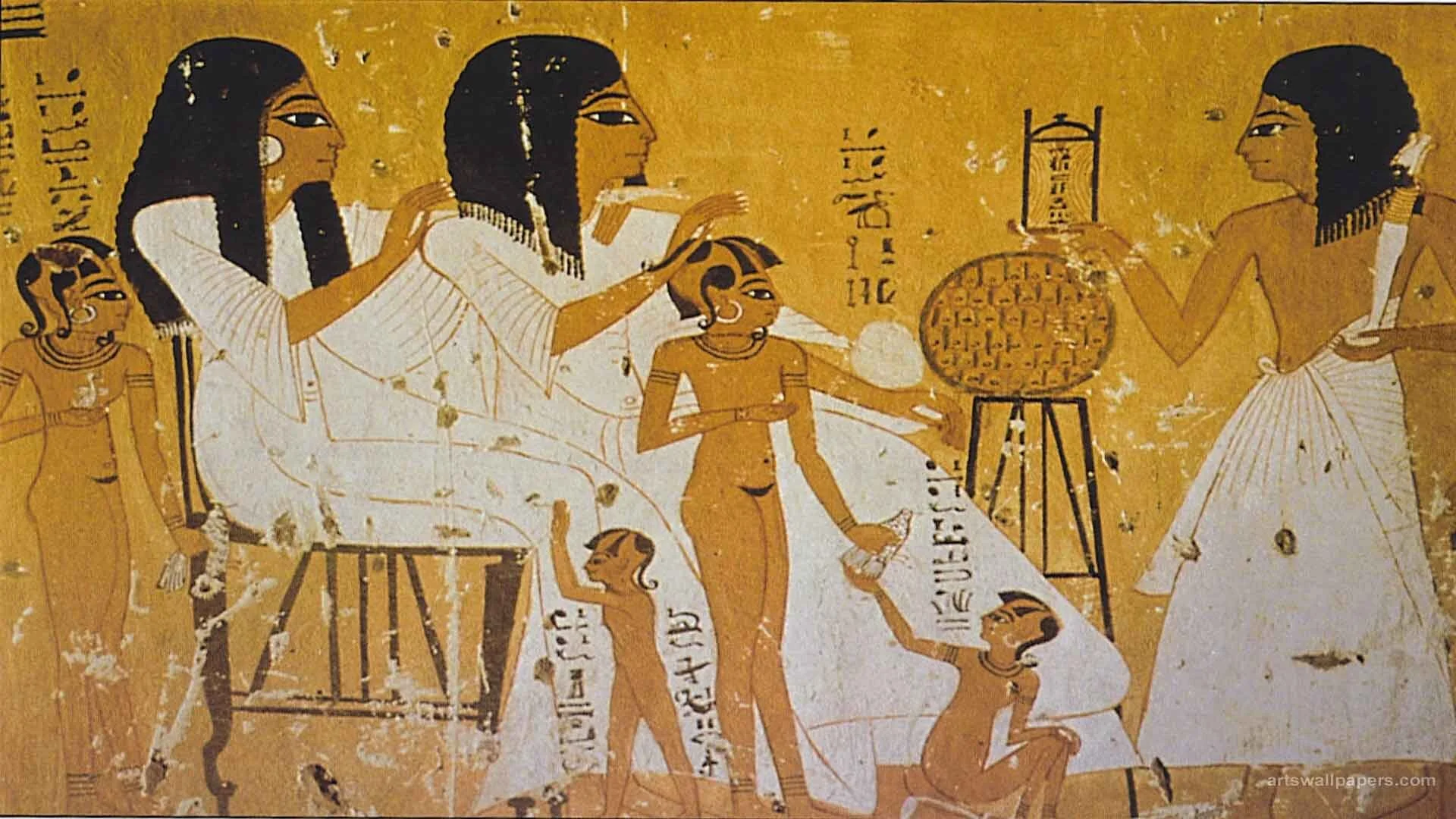

- Social (status & profession). Fine pleated linen, dyed trims, and gold embroidery marked elites; plain undyed linen marked commoners. Hairstyles, jewelry, and headdresses signalled rank and gender.

- Ritual and symbolic (religion & afterlife). Priests wore immaculate white linen to signify purity; funerary garments and mummy wrappings carried symbolic protection into the afterlife. The way one dressed for ritual scenes was as crucial as what one wore every day. Evidence of funerary costume and ritual textiles underscores clothing’s spiritual role.

Materials and production

- Linen— the staple textile. Flax fibers were retted, spun, and woven into linen of different weights; finer linen was required for elite garments and ritual uses.

- Dyes and ornamentation — while many garments remained pale, the elite used colored threads, gold leaf, and decorative embroidery. Faience beads and inlaid collars added color and shimmer. Examples of broad faience collars in museum collections show the artistry of beadwork and color.

- Accessories & construction — belts, pleating, and simple fasteners refined the draped look into more stable garments; by later periods fine pleating and fitted elements appear in art and fragments.

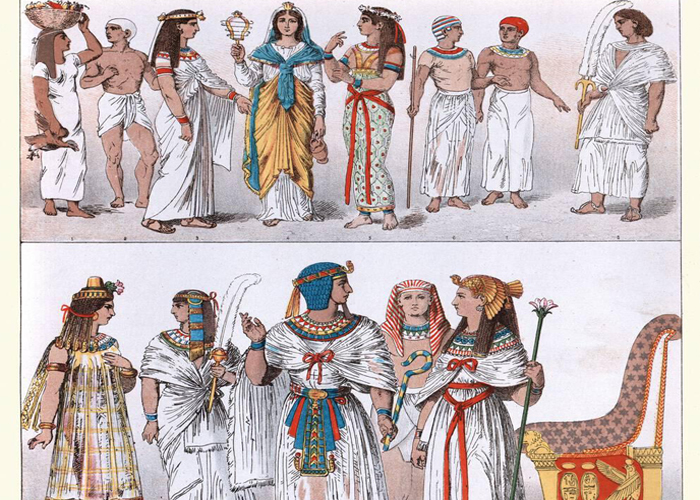

Everyday garments and who wore them

- Workers and peasants: short kilts or simple wrapped skirts, practical and unadorned.

- Women: often wore a sheath dress (kalasiris), a tube-like garment sometimes held with shoulder straps or narrow sleeves — functional but varying by class.

- Elite men and women: wore finely pleated kilts, layered dresses, sashes, and decorative belts; elites also wore sandals and jeweled accessories.

- Priests: strict white linen as a symbol of ritual purity and separation from common life.

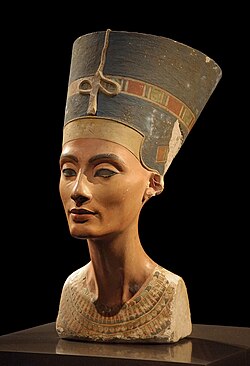

Royal regalia and visible power

Pharaohs and high elites used specific regalia to express divine rule: crowns (the double crown uniting Upper and Lower Egypt), the Nemes headcloth, ceremonial collars, and jeweled pectorals. Portraits and sculptural idealizations (for example, famous royal busts) reflect an aesthetic of ordered, idealized beauty used to project authority.

Jewelry, amulets and protective dress

Jewelry served both adornment and magic — broad collars, bracelets, and amulets (ankh, scarab, Eye of Horus) were worn to display rank and offer supernatural protection. Many pieces were made of gold, faience, and semi-precious stones; museum collections preserve spectacular examples of concentrated color and craftsmanship.

Wigs, grooming, and cosmetics

Grooming was essential: wigs (made from human hair or plant fiber), shaved heads for cleanliness, and perfumed oils were common.

Kohl — the dark eye liner — had practical benefits (reducing glare) and ritual meaning, and kohl implements are common in archaeological finds.

Funerary clothing and the afterlife

Clothing extended into death: mummy linens, funerary garments, and burial collars formed part of the journey to the afterlife. The famous funerary mask and associated burial clothing are the ultimate expression of how dress and ornament belonged to both earthly rank and eternal identity

How fashion evolved (brief timeline)

- Early Periods: wrapped textiles and simple garments.

- Middle Kingdom: improvements in weaving and more refined tailoring.

- New Kingdom: elaborate pleating, richer ornament, and wider use of decorative bead collars and jewelry. Over time, clothing moved from purely functional toward richer, socially coded systems of dress.