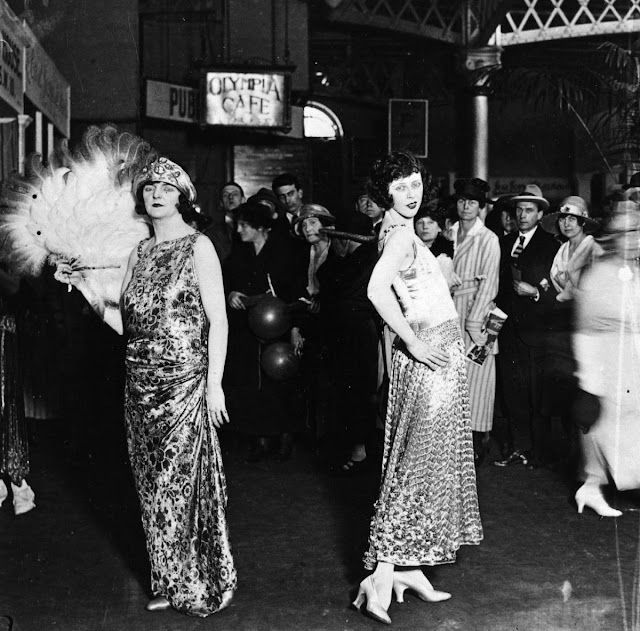

Historical Context: The Great Depression and Its Impact on Fashion

The 1930s were shaped by one of the most challenging economic eras in modern history — the Great Depression, which began with the stock market crash in 1929 and lasted through most of the decade. This economic collapse affected millions of lives worldwide, forcing people to cut back on spending and rethink daily priorities. Clothing was no exception. Fashion shifted from the frivolity of the Roaring Twenties to a more practical and emotionally comforting approach.

Fashion in the early 1930s wasn’t just about style — it became a way for people to cope with hardship. While most households had limited income, looking neat, respectable, and well-dressed was still important. A well-made dress could be worn many ways, altered over time, and passed between sisters or friends. This era emphasized resourcefulness: garments were repaired, taken in, let out, and re-styled to last as long as possible.

Designers reacted to the economic climate by emphasizing quality over quantity, craftsmanship over ornament, and silhouettes that conveyed dignity rather than extravagance. In magazines and fashion plates, the message was clear: clothing should be versatile, enduring, and elegant even in simplicity.

The Return to Femininity: Sculpted Silhouettes and Grace

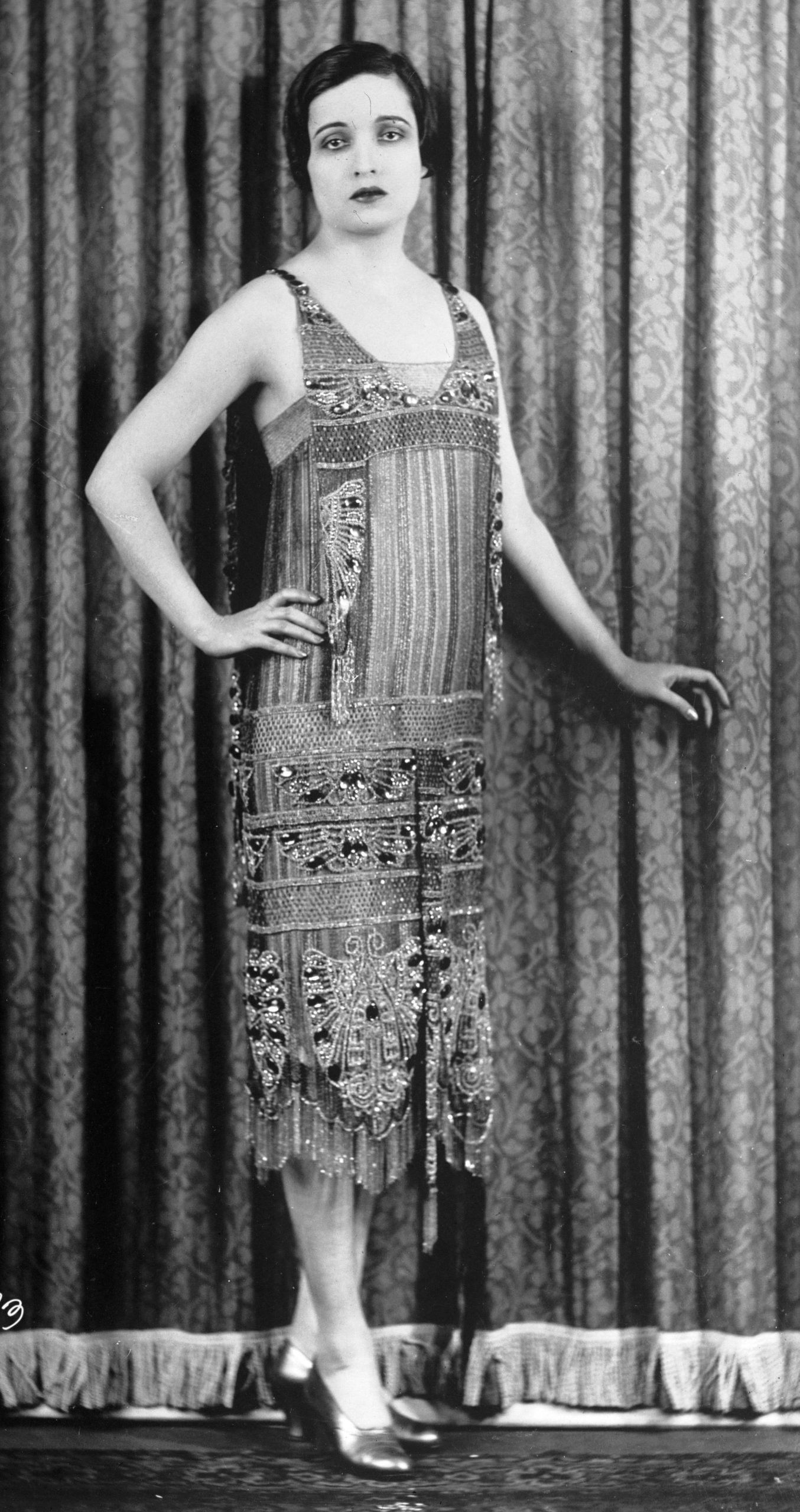

After the straight, boyish silhouettes of the 1920s, the 1930s brought back a celebration of the female form. Rather than rejecting curves, fashion began to enhance them gracefully. Skirts became longer, often falling mid-calf or down to the ankle. Waists re-established their place on the body, not exaggerated but subtly defined. Shoulders were softened, and necklines offered gentle, flattering shapes that elongated and refined the figure.

The overall effect was not bold or flashy but quietly elegant and refined. Dresses were designed to move with the wearer, to catch the light, and to create a sense of fluidity in motion. Unlike the angular look of the previous decade, 1930s silhouettes moved toward smooth, flowing lines that emphasized verticality and poise.

This return to femininity wasn’t about glamour alone; it was about emotional reassurance. In clothing, people found a way to express resilience, optimism, and inner strength.

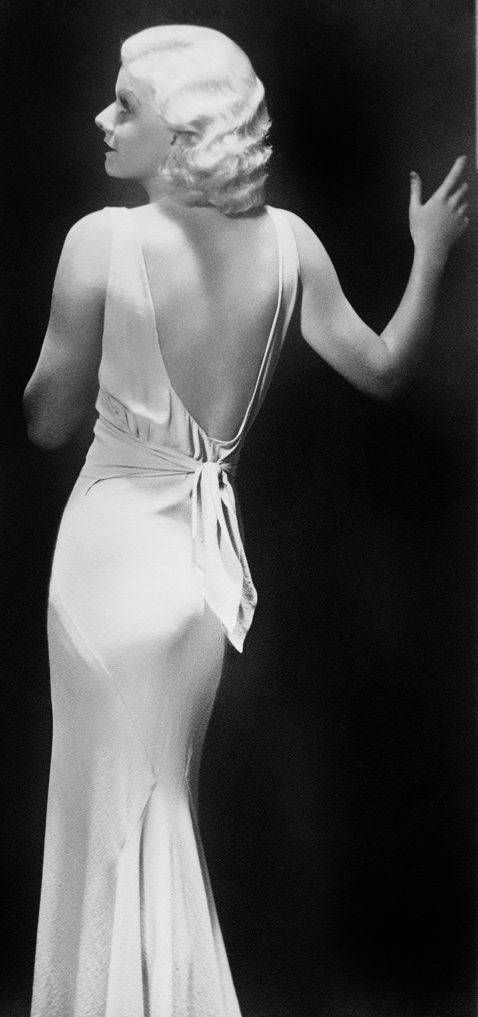

Bias Cut: Revolutionizing Dressmaking

One of the most significant innovations of 1930s fashion was the bias cut — a method of cutting fabric diagonally across the weave rather than along the straight grain. This technique allows fabric to stretch, drape, and cling naturally to the body, creating a silhouette that feels almost alive.

What the Bias Cut Did:

- Allowed dresses to follow body curves without darts or structure.

- Created garments that moved fluidly and elegantly with every step.

- Used even on simple fabrics to produce sophisticated, sensual forms.

Designer Madeleine Vionnet is credited with mastering and popularizing this technique. Through the bias cut, she transformed simple lengths of fabric into gowns that looked effortless yet incredibly refined — a kind of wearable sculpture. These dresses defined 1930s style and had enduring influence on couture and ready-to-wear fashion.

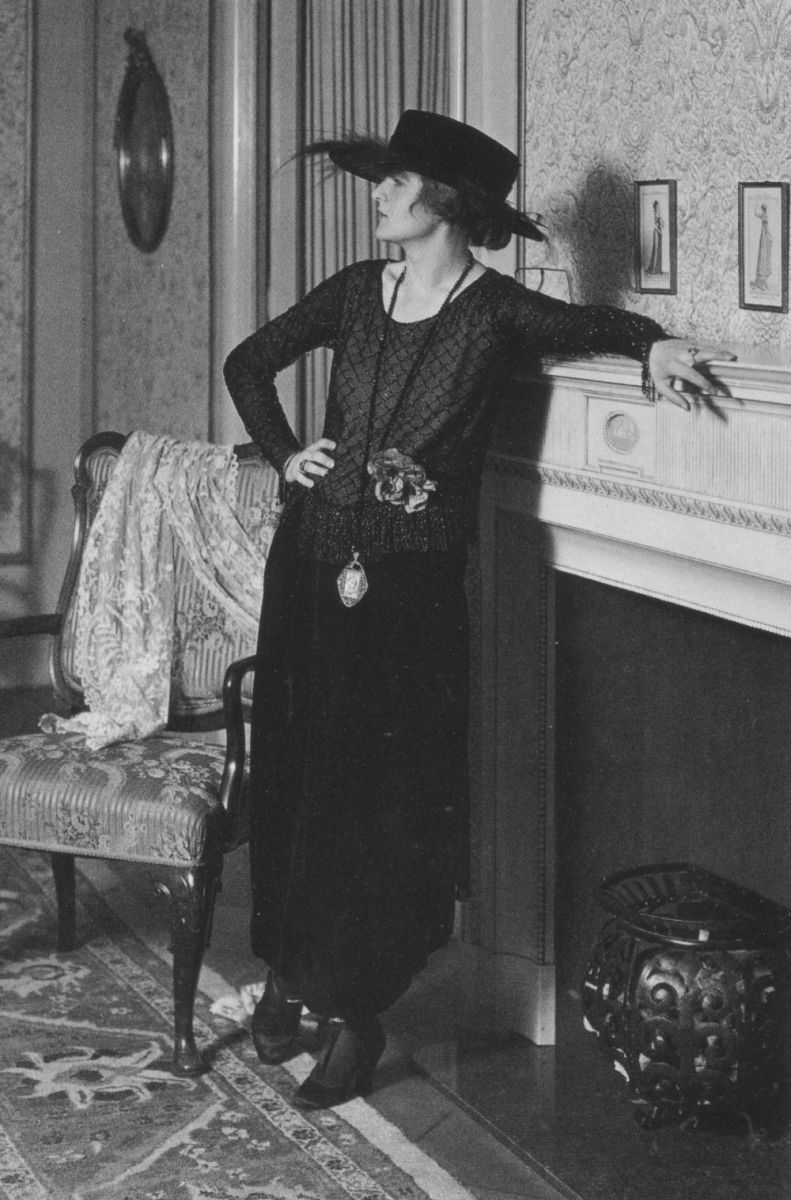

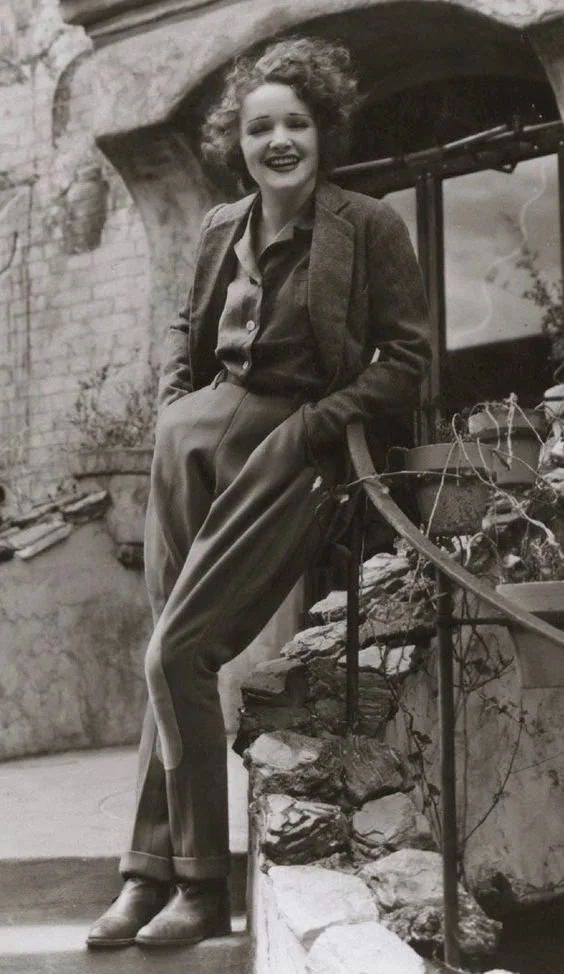

Daywear: Modesty, Practicality, and Everyday Elegance

Everyday clothing in the 1930s was shaped by necessity. While couture gowns sparkled on film and in evening magazines, most people needed practical, comfortable, and durable clothes for daily life.

Typical Features of 1930s Daywear:

- Mid-calf length skirts — a compromise between modesty and ease of movement.

- Modest necklines and soft tailoring — respectful yet refined.

- Blouses paired with skirts or tailored suits — separates that could be mixed and matched.

- Neutral and muted colors — practical for wear and easy to coordinate.

Women often wore light jackets, knit cardigans, and simple belts to define shape without excess fabric. Because clothing was expensive relative to income, garments were altered and reused, passed down between siblings, and styled in multiple ways.

Daywear in the 1930s combined comfort, structure, and understated beauty, reflecting both economic reality and a desire for emotional steadiness.

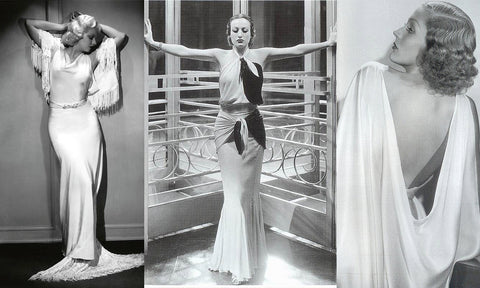

Eveningwear: Hollywood Glamour and Aspirational Style

While everyday clothes were restrained, eveningwear in the 1930s embraced glamour and fantasy. Cinema played a central role here: Hollywood films offered escapism, and the wardrobes of movie stars became the ultimate style references for women around the world.

Elements of 1930s Evening Fashion:

- Floor-length gowns that elongated the silhouette.

- Luxurious fabrics such as silk satin, chiffon, and velvet.

- Draped backs and sleek fronts for dramatic yet refined elegance.

- Minimal ornamentation — design focused on cut and movement rather than excessive decoration.

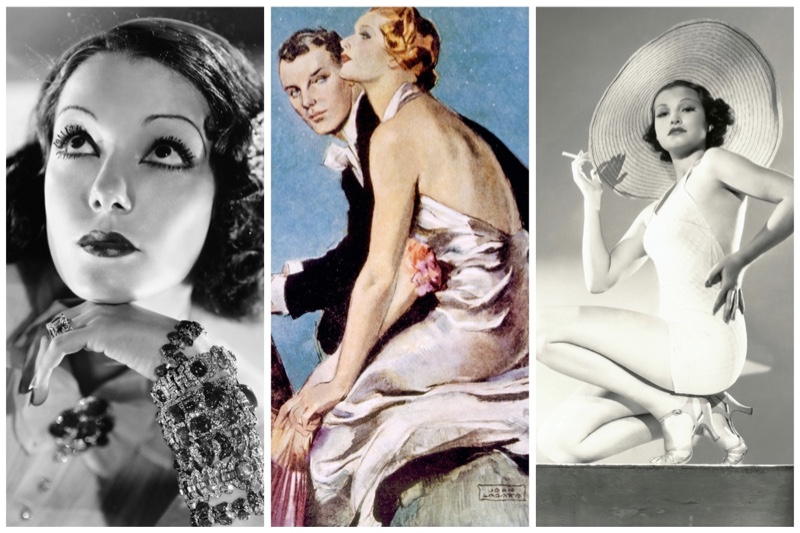

Stars like Greta Garbo, Joan Crawford, and Jean Harlow were seen as embodiments of 1930s chic. Their on-screen wardrobes were powerful aspirational tools that helped women through difficult times by offering a glamorous vision of possibility.

Eveningwear became not just clothing — it became a symbol of emotional resilience and beauty under adversity.

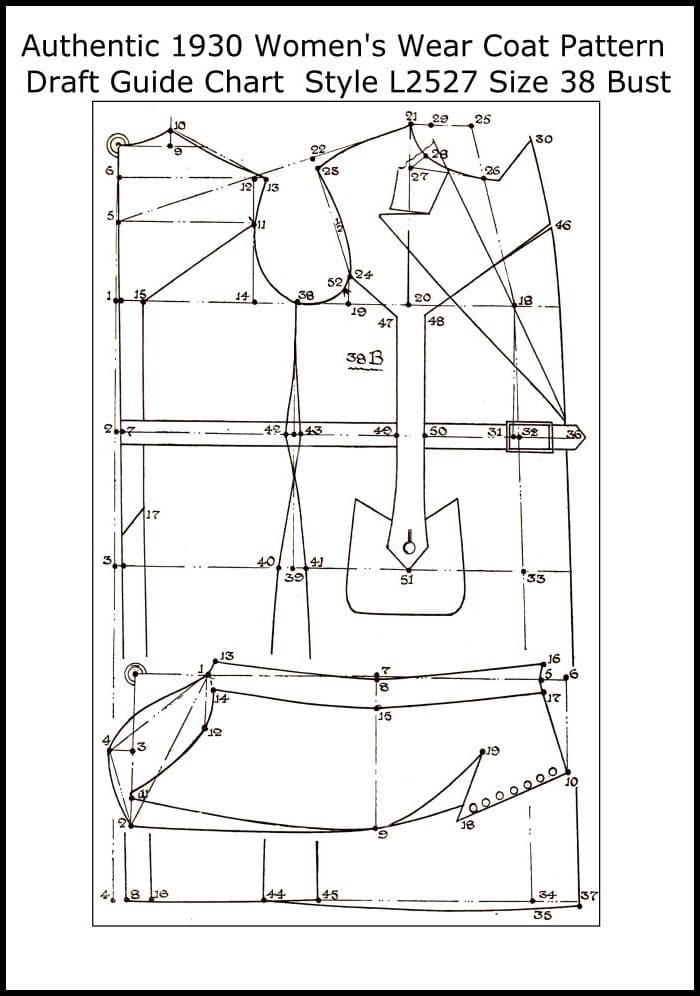

Construction Techniques: Tailoring, Draping, and Silhouette Craft

Fashion in the 1930s valued how garments were made as much as how they looked. Ornament took a back seat to thoughtful engineering of fabric and form.

Key Terms in Fashion Construction:

- Silhouette — the overall shape or outline of a garment. In the 1930s, silhouettes emphasized vertical, elongated lines.

- Draping — the process of positioning and pinning fabric directly on a form (mannequin) to achieve the desired flow and contour.

- Tailoring — precision cutting and stitching to shape a garment so it fits the body just right, often involving interfacing, seam shaping, and careful hemlines.

Designers used these techniques to achieve elegance without relying on large quantities of material. A bias-cut gown, for example, could appear extravagant without needing heavy trims or jewels. The sophistication was in the engineering of simplicity.

Hairstyles and Beauty Ideals: Graceful, Polished, Mature

Hairstyles in the 1930s reflected the decade’s overall aesthetic: refined, graceful, polished. Unlike the rebellious cropped bobs of the 1920s, 1930s hair was often short to medium length but styled close to the head.

Popular Hair Trends:

- Finger waves — smooth, sculpted waves that framed the face.

- Soft curls — neat, controlled curls that suggested elegance.

- Side parts — creating a gentle, flattering asymmetry.

Makeup emphasized clarity and poise: thin, well-arched eyebrows, smooth luminous skin, and lips tinted in muted reds or berries. The overall look was mature and composed, aligning with the era’s preference for subtle, controlled beauty.

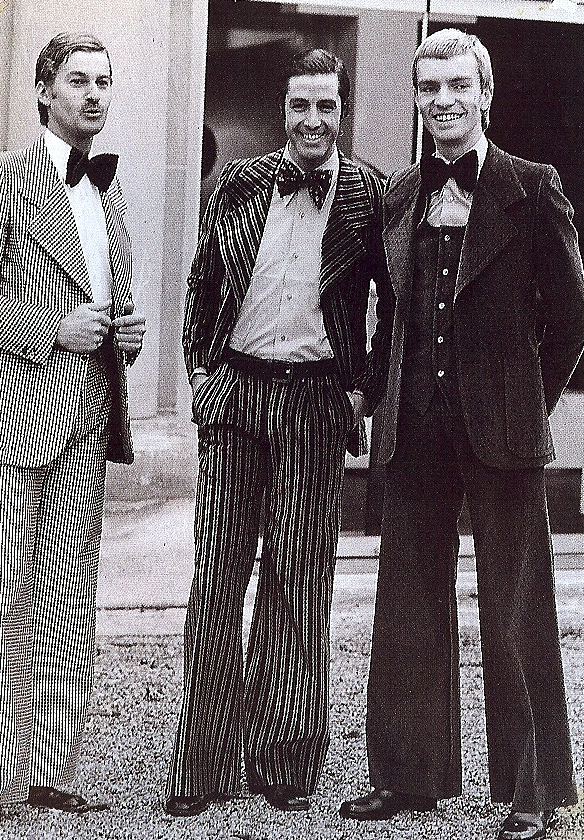

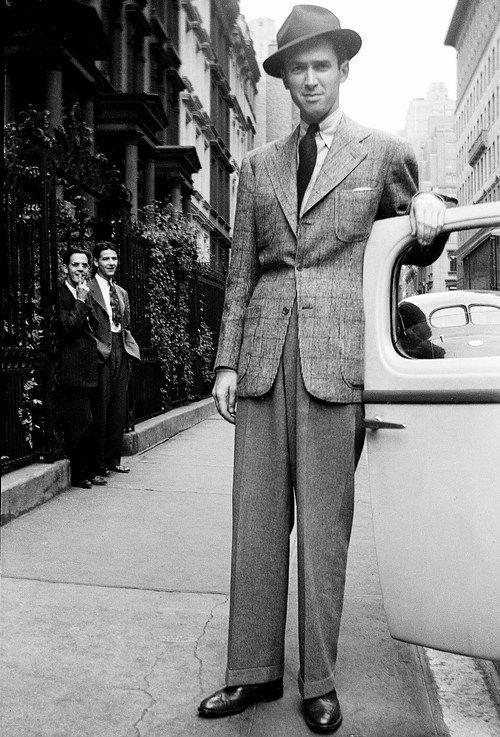

Men’s Fashion: Strong Shoulders and Structured Style

In men’s fashion, the 1930s were defined by structure, authority, and precision. Clothing had to convey strength and professionalism in a time of instability.

Hallmarks of 1930s Men’s Style:

- Double-breasted suits with broad, padded shoulders.

- High-waisted trousers that lengthened the line of the leg.

- Longer jackets creating a commanding silhouette.

- Fedoras and structured hats as signature accessories.

Colors tended toward neutrals and deep tonal shades: charcoal, navy, olive, and deep browns. Men’s fashion balanced practicality with stately elegance, projecting confidence and seriousness appropriate for the era.

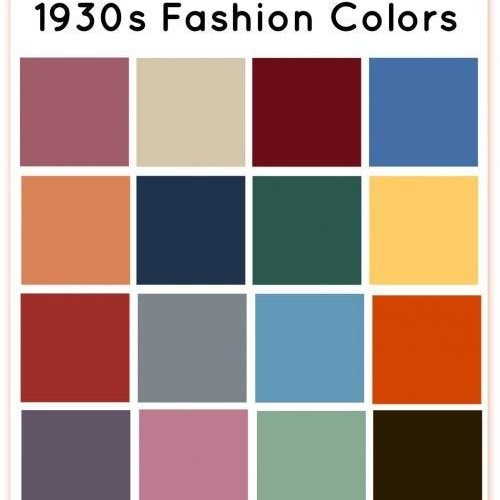

Materials, Color Palettes, and Economic Realities

Economic limitations shaped the materials people wore. Luxurious fabrics were still used — but sparingly and often reserved for eveningwear or film costumes.

Common Fabrics:

- Rayon — a silk substitute that became widely popular.

- Wool and wool blends — durable and warm for everyday wear.

- Cotton and linen — practical for day garments and casual attire.

Typical Colors:

- Neutral tones (beige, grey, taupe)

- Earth tones (browns, olives)

- Deep shades (navy, burgundy)

Bright or pastel colors were rare in everyday wear but appeared more often in evening fashion, where designers used color strategically to enhance mood and elegance.

Legacy of 1930s Fashion: A Balance of Practicality and Beauty

The fashion of the 1930s left a lasting influence on the history of style. It demonstrated that elegance does not require excess, and that beauty can coexist with practicality. Techniques like the bias cut continue to shape haute couture, and the decade’s emphasis on form, movement, and refined silhouettes remain central to modern fashion.

The 1930s taught designers and wearers alike that clothing can be a source of emotional strength, personal identity, and artistic expression, even in times of hardship.